From Field to Broadcast Booth to Fishing Boat, There’ll Never Be Another Jimmy Piersall

Jimmy Piersall was a pioneer, though not many have followed the path he forged over six decades ago. At the time, Piersall was viewed as a clown and an oddity, much of which was his own doing. His antics were part manifestation of his bipolar disorder and part his out-there, take-it-or-leave-it attitude. Whether it was his opponents, his teammates, or the propriety of the game, this was a man who pulled no punches and gave no damns what people thought.

Over the course of a decorated 17-year career with the Red Sox, Indians, Mets, Senators, and Angels, Piersall feuded with just about everyone. He mocked teammate Dom DiMaggio’s running style, danced wildly on the basepaths when facing Satchel Paige — one can only imagine what he’d have done against Jon Lester — and fought with Billy Martin. His fiery personality may have burned a few bridges, but it also galvanized many friendships.

Beneath the boisterous persona, Piersall also battled a crippling fear of failure that was only exacerbated by his mental illness. After a demotion to the minors in 1952, he suffered a nervous breakdown and was admitted to a mental hospital, where he spent six weeks undergoing shock treatment and intensive counseling. He was eventually treated with lithium and was able to return to the majors, winning a pair of Gold Gloves and being named to two All-Star teams.

Following his playing career, Piersall joined Harry Caray in the White Sox broadcast booth, which you can imagine — or maybe remember — was an incendiary and incredibly entertaining combination. My father-in-law, a huge Sox fan, told me stories about how Caray used to frequently jab Piersall with references to his (in)sanity. That line of employment ended for Piersall when he criticized players and made comments about owner Bill Veeck’s wife.

To his credit, Piersall totally owned his struggles, even when he couldn’t always contain them. He knew who he was and didn’t apologize for it. Like Caray, he too headed to the Cubs organization in the 80’s, joining the team as an outfield instructor. That relationship lasted until 1999, over which time Piersall impacted a generation of young players. Ryne Sandberg and Andre Dawson were among those who remained close to Piersall and credited him with helping them become better defenders.

Piersall’s story was chronicled in a book, Fear Strikes Out, that was turned into a 1957 movie by the same name in which he was actually portrayed by Anthony Perkins, who would go on to star in Psycho. I can’t say for certain, but given his own admission that he was nuts (his words), I think the movie’s muse would’ve laughed at the irony of that role. Though he was proud of the book, Piersall hated the movie because of the fictionalized events they added and the fact that Perkins “threw like a girl.” (Again, his words.)

That his personal struggles were so highly publicized is really quite remarkable when you think about it, particularly considering the stigma that still surrounds mental illness today. Being able to bring such topics into the light in the 1950’s — and in the realm of the national pastime, no less — is nigh unbelievable.

In the wake of his passing Saturday at the age of 87, a lot of stories have been written about James Anthony Piersall, most of which are like what you just read above. Perhaps they recounted the shenanigans or the hot temper, maybe even marveled at his ability to play at such a high level while combating demons few others understood. But when Cubs Insider was presented with an opportunity to share a few more personal tales, we jumped at the chance.

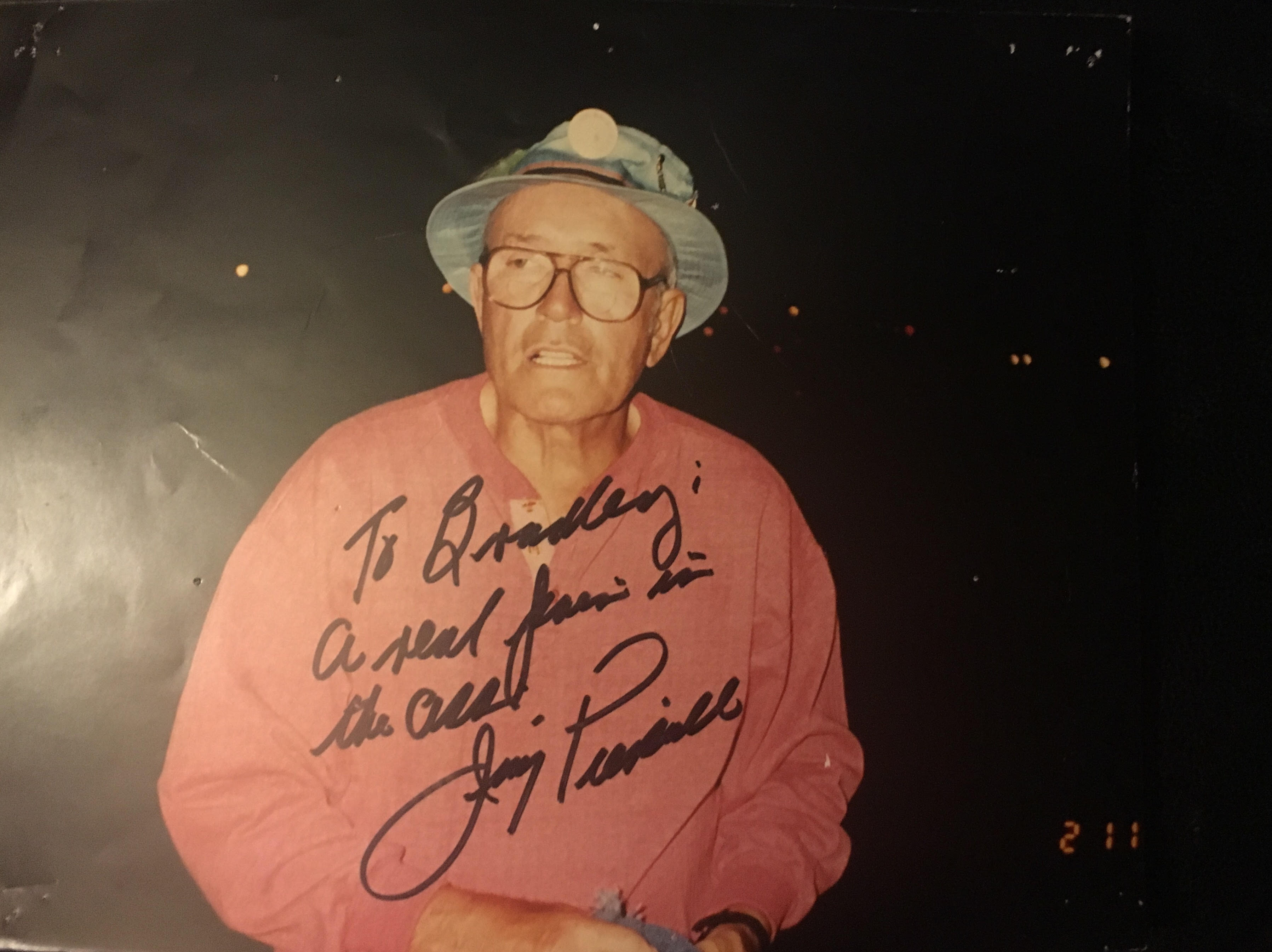

Brad Pogofsky is the son of the late Larry Pogofsky, member of the White Sox board of directors, and is also an acquaintance of our Jon Strong. The elder Pogofsky befriended Piersall during his days as a broadcaster and Brad knew Jimmy as something of a godfather. When Brad attended school in Arizona, he spent a lot of time with Piersall and his wife Jan, who was a steadying force for the colorful character.

By that time, the wacky on-field antics were well in the rearview mirror. But the fire was still there, as was the passion for baseball.

“He was an outfield coach with the Cubs for most of the time that I was in Arizona,” Pogofsky explained. “He was very proud of his students, the guys that he was teaching. He won two Gold Gloves, [but] he really didn’t have them up. They were in the basement. He was very down-to-earth, didn’t have memorabilia hanging all over his house.

“His favorite thing to do was to go fishing, and I would go fishing with him many times in Arizona. He had his routine: we’d go fishing and then he’d be home by a certain time and get all his notes ready to prepare for the radio show that he had at the time [on 670 The Score]. He’d get home and he’d read up all his information and make sure he was ready for his radio show. When it came to baseball, no one knew the prospects and the kids like him.”

“He was very close with his wife, who was absolutely an amazing person who he was really lucky to have. She really looked after him and they were really good together. He also had a shar-pei dog. I don’t remember its name, but the dog was probably one of his favorite things in the world.”

Sounds like a different guy from the one described at the outset of this piece, doesn’t it? But don’t think for a minute that Piersall had grown completely docile as he matured.

“I don’t want to say he was laid-back, because that wouldn’t be the right word,” Pogofsky said. “He just loved baseball and loved to fish and that was his life. He didn’t drink alcohol, he never drank.

“But he had one of those personalities, I remember when I was a kid I said something to him and he chased me upstairs with a baseball bat. He was an intense guy. Even when we were fishing, he’d be like, ‘Dammit, screw this, we’re moving.’ One time he was on a boat with my dad and he was picking up the anchor and moving it every five minutes.

“Jimmy said what was on his mind, he didn’t care about the consequences, and that was him. He wasn’t going to cater and bend over to corporate sponsors and that’s the way he was. He said, ‘This is who I am, accept me or don’t accept me.'”

As we talked, I began to get the sense that Jimmy Piersall was a little like some of the friends I’ve had over the years, one of those guys who you want to punch one minute and hug the next.

“He was close with Ted Williams, he was close with Dom DiMaggio. And I’ll tell you he was very close with Harry Caray up until the day he died. They were very close, even after Jimmy was done with the broadcasting. He was a good friend to my dad and my family, he was a good friend to me, and he’ll be missed dearly.

“He was a fiery guy, one of a kind. There’ll never be another Jimmy Piersall.”

You can say that again. In a sport long known for its characters, Piersall was easily one of the brightest and most colorful. Perhaps that’s because he was also one of its darkest at the same time, his illness providing shadows from which his personality stood out in sharp relief.

Baseball needs more people like this, folks who aren’t afraid to be who they are and, even more importantly, who won’t shy away when who they are doesn’t fit who others think they should be. I regret that I never got the chance to meet Piersall, to experience that fire and pick that unique brain. But I’m glad I was able to learn a little more about him from one of the people who knew him best.

Godspeed, Jimmy Piersall, may you trot backwards through the Pearly Gates.