Griffey, Piazza, and the Dying Mythology of Baseball

Perseus; Sisyphus; Theseus; Prometheus; Icarus; Ruth; Williams; Mays; Banks.

The Greek names are so fitting because legends, myths, are all of us. Yet they’re also none of us, their feats too grand to be accomplished by mere mortals. From slaying monsters to pushing rocks up mountains in eternal struggle, to bringing fire to flying too close to the sun, those stories of old tell of men aided by gods in tasks none thought possible. Or maybe they got caught trying to play like the gods, to do things man was never meant to do.

Myths often attempt to explain that which the mind can’t comprehend, growing taller over time as they’re retold in the absence of corroborating evidence. Did you know that if you tell a tale 42 times, it’ll be tall enough to reach the moon? 103 times and it’ll get as thick as the universe. Babe Ruth called his shot, Ted Williams could smell the bat smoke from hitting the ball just right, and Willy Mays once hit a line drive through an outfield wall. Are those all true? Does it matter?

Not really. Well, maybe. The mythologizing of individual players doesn’t matter so much as the minstrels plucking the strings, singing the songs, and casting the ballots, and many of those folks are clinging fast to the oral traditions of the past. When I first read that aforelinked Neil Paine piece, it stoked the fires of my disdain for the Hall of Fame voting process, but I have since cooled and shifted a bit in terms of how I view it.

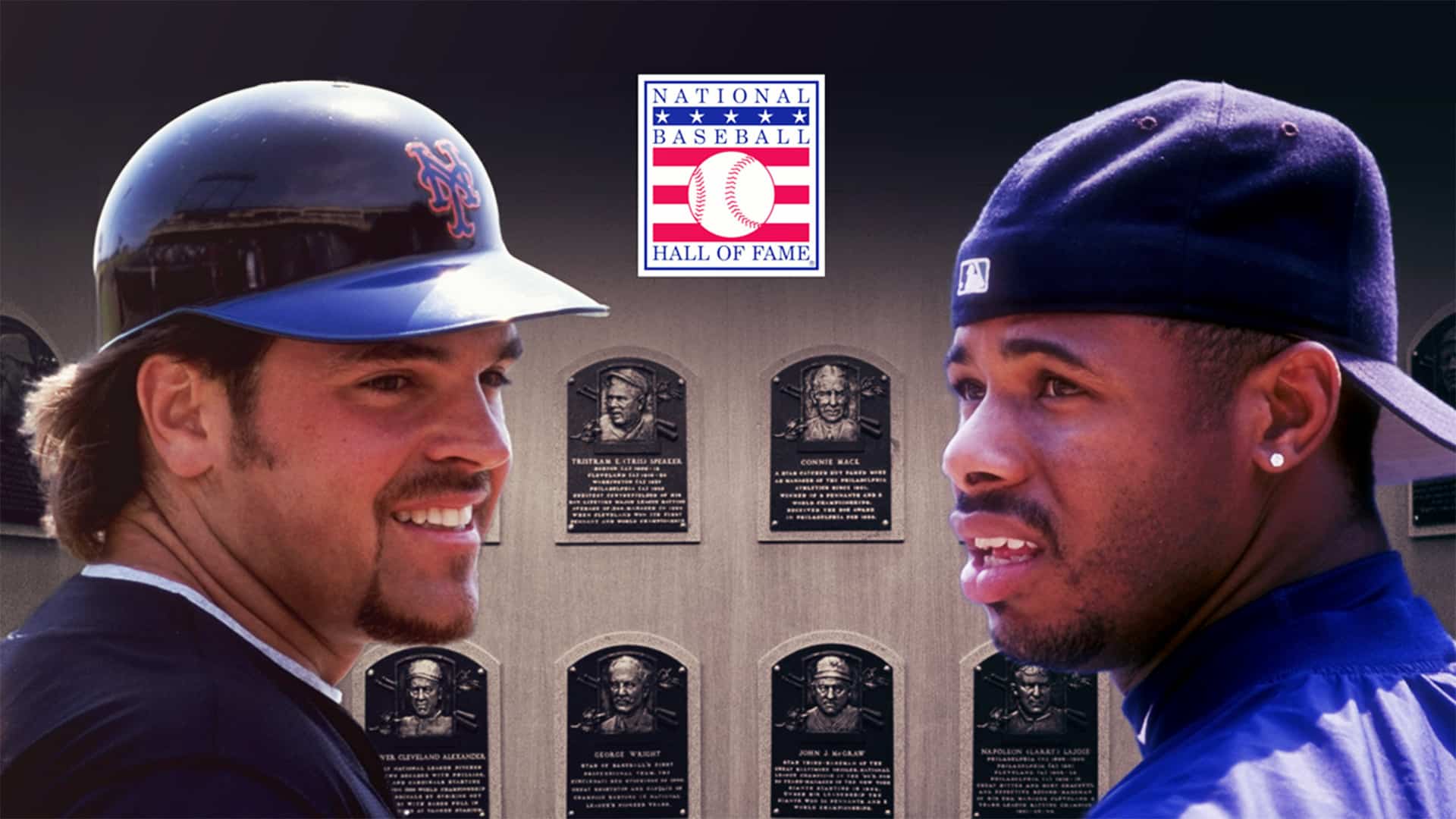

As I followed the voting results last night, I saw more and more people waxing nostalgic about Ken Griffey, Jr’s rookie card or Mike Piazza being drafted by Tommy Lasorda in 6,000th round as a favor to Piazza’s dad. Those two players represent some of the last of an elite vanguard of players made larger than life by word of mouth, at least for those in my generation.

Griffey had the thousand-watt smile, backwards hat, and the perfect swing that Nike turned into a logo. He was Michael Jordan in a baseball jersey, only he was way better than Michael Jordan in a baseball jersey. Mike Piazza had a pretty swing of his own, quickly establishing himself as the best power-hitting catcher of all time. But perhaps his greatest accomplishment was the ability to wear a fu manchu without so much as a trace of irony. The beard game is all the rage now, but Piazza was a pilose pioneer at the forefront of facial fleece.

I certainly don’t mean to insinuate that the numbers weren’t worthy — they certainly were by any measure in any era — only that there came a point at which I/we stopped viewing major leaguers as super heroes. I attribute most of that to age, but I suppose due credit should be given to increased access. How I see things as a grown man is not how I saw them as a child, so my perspective has changed quite a bit. Additionally, the fact that I can actually see all of the exploits of today’s stars in real-time kinda makes them seem less, I don’t know, ethereal.

There’s really no line of demarcation for this either, as I’d imagine each individual observer is going to see players in different lights. And there are some athletes who transcend the humanization of even the most pragmatic among us. Kris Bryant might be one such player, grazing as he does with the few remaining unicorns the game has to offer. I know I tend to view Bryant with a bit more awe than I afford to others who are older and more well established.

Please don’t take this as the lament that I realize the headline may make it seem to be. It’s just that as I looked over the list of HOF-eligible players again and again and saw the names there, I found myself moved more by statistics than emotions. That’s not a bad thing, just a shift in perception, and kind of a bittersweet one at that. I’m being forced to grow up and recognize my own mortality as a result of seeing it in the stars I watched play the game.

I recently read a fantastic piece from ESPN’s Bill Barnwell about his weight loss journey after a lifelong struggle with body image and food addiction, and something in there really struck me. He spoke of taking no joy in eating, of acting out of compulsion. Once he had changed his bad habits, however, he found himself able to take pleasure in good food (in moderation, of course) once more.

Likewise, giving up the excessive adulation of athletes has allowed me to better appreciate how special their elite talent really is. Bearing in mind that Barnwell’s situation is obviously much more consequential, the analogy felt apropos. I still believe in magic, it’s just that I’ve tempered it with a few helpings of practicality. And I’m pretty cool with that.